English | French

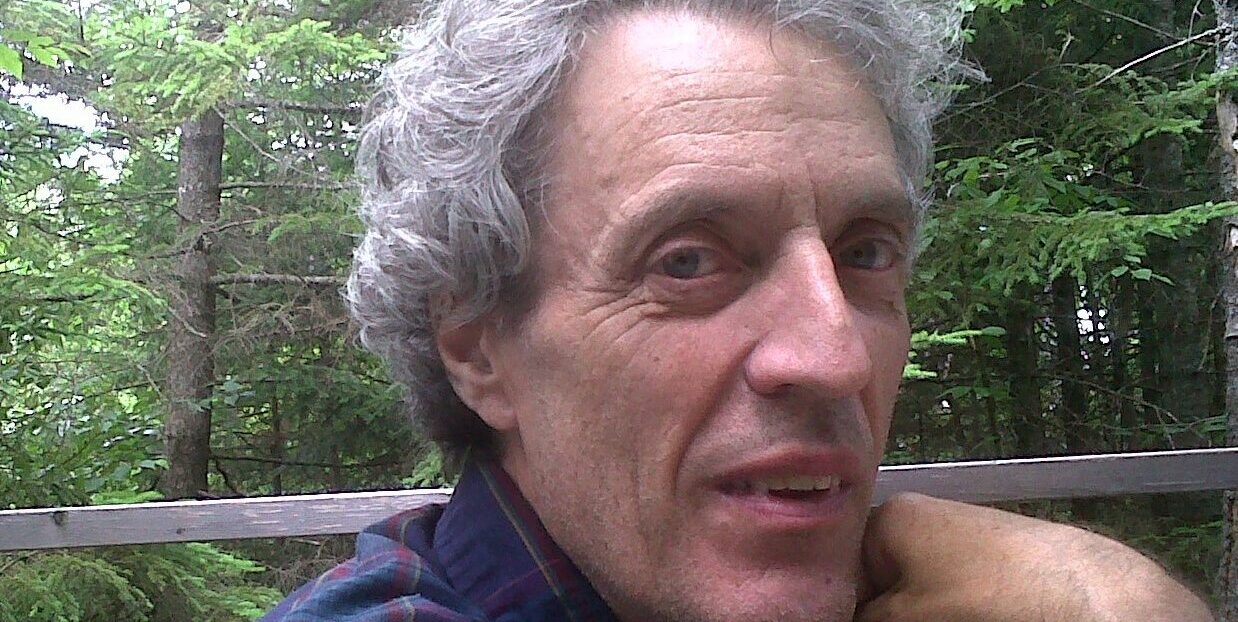

Algonomy is the name of a discipline for the systematic study of suffering, proposed by Robert Daoust. The Algosphere Alliance, launched by Robert and others in 2011, is an open and transparent global network of individuals and organizations, dedicated to alleviating suffering.

Sentience Research: You are one of the founders of the Algosphere. How did the organisation start, and what were its foundational principles?

Robert Daoust: To my great surprise, I realized in 1975 that there was no central place in our culture where one could go to deal with the phenomenon of suffering itself, in all its variety or aspects. I then proposed the creation of a theoretical discipline and a practical enterprise. In the following decades, I found that people in general had sympathy for my proposal, but no one got involved with me until 2011, when Jean-Christophe Lurenbaum and I met through David Pearce’s mediation. Jean-Christophe also had in the seventies the idea of organizing the alleviation of suffering in the world; for that purpose, deliberately, he studied in public economics and then chose to work as a secretary for strategy at the largest French public corporation before retiring early, going back to university and writing a book summarizing his ideas. Mines were in a 1986 document called L’organisation générale contre les maux.

Thanks to Jean-Christophe’s great expertise, the Algosphere Alliance was started in 2013. It is a unique kind of institution, open to all those for whom the alleviation of suffering is a priority. It has no registration in any jurisdiction (it is free from any external authority), no power structure (no place for ego or power trip), no money (no control by the wealthiest), no obligation imposed on participants (contribute as you wish) and it is designed to operate slowly, methodically, for centuries and for very large-scale changes, more than in the heat of each passing emergency. It does not act by itself to alleviate suffering but rather through its allies, each in their particular fields of interest.

Sentience Research: What is the main feature of the Algosphere that makes it different from other projects?

Robert Daoust: The Alliance proposes a convergence of forces at the most abstract level of generality that can bring together the diverse actors dealing with the alleviation of suffering — and that abstract level is in my opinion the most concretely powerful in practice because it radically simplifies the approach to suffering. To say it more clearly perhaps, you and I do our things but can get into synergy by taking decisions together that are mutually advantageous, and we all can do that collectively thanks to the meeting place offered by the Alliance, the Agora. The Agora works as a worldwide direct democracy tool, a decentralized and transparent decision-making process that is based on consent, i.e. non-disagreement, i.e. non-suffering.

Sentience Research: What happened before that? In your biographical notes we can read depressing thoughts of teenage Robert about suffering, “Extreme pain endured by innumerable beings in their march across life appears to me like a hopeless persecution perpetrated by inhuman forces which we must absolutely defeat.” Has this changed in time? How do you actually experience personally and assess globally suffering in the world?

Robert Daoust: How much suffering is there? Personally, my mother died when I was two years and a half, but I realized only recently that this was, for real, a painful tragedy. I mean… this made my life, and several other lives too, complicated and full of hardship, but that death never felt painful to me. I first encountered excessive suffering when I was ill with various common childhood illnesses, and from the age of ten I did all I could to avoid physical pain. Similarly, in my late twenties, I progressively learned to avoid psychological suffering due to causes such as depression or sexual frustration. After that, I have mostly been happy. Anyhow, it is not clear to me how someone can assess the amount of suffering that occurs in oneself, let alone in the whole world. We need an algometry, a science of suffering quantification, a subspecialty of algonomy. Roughly, I think that the amount of suffering on earth has been more or less equal during the last million years. I cannot look at the hellish state of the world without what I call welder’s goggles. I take solace, however, in this sentence from Maus, where Spiegelman’s father, a holocaust survivor, says about his stay in Dachau: “And that’s where my troubles began”. That was after he had been in Auschwitz for a long time!!!

Sentience Research: You say that “all major spheres of human activity deal in one way or another with suffering”, although it is not their main concern. Is this not a paradox or contradiction?

Robert Daoust: Do you see a contradiction?

Sentience Research: I mean, suffering is ubiquitous in human lives (and in other animals too, of course) and yet there have hardly been any humans who have set out to end suffering. It seems as if most accept it as a necessary or inevitable evil.

Robert Daoust: Oh, yes! Before Newtonian science you could deal with gravity but only up to a certain point. It takes a lot of abstract thinking to get beyond the obvious and start discovering what else can be done, like going to the moon. It is only with the advent of a new scientific psychology in the 21st century, I believe, that we will really begin to understand how to escape the gravity of our suffering condition. I noticed also that, by definition so to speak, the more something is needed, the harder it is to get it. That is because, I guess, we are in a world where each entity competes for its own construction, its own growth. Cooperation instead of competition occurs when one level of activity is unexpectedly surpassed by another level of activity, as it has occurred throughout the history of biological evolution, and of human evolution as well. That explains perhaps, but not very clearly, sorry, why it is so hard to find collaboration for projects like mine…

Sentience Research: The idea of a discipline that has suffering as its main focus, algonomy, is something that has matured in you for many years. (It has been in your head at least since 1975!) How has it changed since then? What are the challenges of this project?

Robert Daoust: It did not change much. At the start I called it algology. Over the subsequent decade, I spent my time in libraries looking for works or fields of study that already existed in the spirit of algonomy. Alas, and to my unending surprise, I did not find much. In 1986, I produced a summary or blueprint L’organisation générale contre les maux, and around 2000-2005 an Introduction to Algonomy. I should say that from the very beginning, my feeling was that if the idea was as good as it seemed, it would take only two weeks to find plenty of interested people! I still have the same feeling. The last attempt I made was in 2019, when I proposed to create an Institute of Algonomy: it’s easy, all you have to do is find 10 million dollars from one billionaire philanthropist! Of course, that too was not settled in two weeks — because of a lack of audacity, I suppose: not a single request was made to obtain ten millions. A new discipline dedicated to suffering includes a lot of challenges, but I predict that if we could get it off the ground, it would be so successful, in terms of spared sufferings, that its development would be quick and lasting. Sometimes, however, I think all this might be a lifelong delusion… but it’s a bet, a wager: could I imagine a more meaningful way to use my time?

Sentience Research: “Suffering”, “Pain”, “Disvalue”, “Negative Valence”, “Negative Qualia”, “Unsatisfied Desires” and “Frustrated Preferences” are conflicting terms sometimes used ambiguously. Which is your favourite term? Do you use different definitions?

Robert Daoust: My favorite term is unpleasantness, which I retained from my studies in pain science, where it is used to distinguish between various components of physical pain, such as ‘aversion’ (“to not want” is not “to dislike”, cf Berridge) or ‘suffering’ (secondary or tertiary psychological distress). Around 2006-2010, I wrote most of the Wikipedia entry on suffering, and especially the section Terminology. By the way, even this article, which is regularly consulted, has not attracted much collaboration for its edition, which is a pity.

Terminology about suffering is extraordinarily confusing. It reveals how much suffering is a blind spot in our culture. One of the first uses of algonomy would be to adopt a universal technical terminology. Perhaps suffering would be called ‘algo’. So… personally I use only one definition of suffering: unpleasant feeling. I find negative valence interesting, but I think it very often occurs without unpleasantness, like when for instance an inquisitive mind realizes that a piece of information is missing: this may be felt as a disvalue, but within a stream of pleasant exploration. Pleasure and suffering are not the only values that exist, in my opinion, far from it. It might be disastrous to stop all suffering (or to promote all pleasures) if it turns out that some of it is necessary (or is an obstacle) to reach something of great value.

Another use of algonomy, that will bring light into this complex topic, will be to provide a taxology of suffering, a tool for collecting and classifying information concerning the “kinds of suffering, people or animals who suffer, causes of suffering, people and organizations who cause suffering, solutions or strategies relative to suffering, people and organizations who contribute to stop or prevent excessive suffering, documents relevant to the systematic study of suffering,” etc.

Sentience Research: What are your thoughts on the nature of suffering: why do we suffer and how sentient experience is possible in the first place?

Robert Daoust: Ultimately, the nature of suffering or sentience depends on the nature of what exists at the most fundamental level, beyond our current knowledge. So, we are left to wonder what this world is and what value it has. Philosophically, I choose sanity, I believe and hope that the unknown will become known someday and most importantly, that it will not turn out to be “too” bad: in all likelihood there is no eternal hell or something even worse. My view is that we live in the universe described by modern physics, which consists of matter-energy or waves-particles. Contemporary science is in the process of discovering how sentience emerges from matter-energy, and as a consequence it will understand much better itself and its concepts like space-time, matter-energy, mathematical objects, linguistic objects, etc.

Sentience Research: Did you reach any conclusions regarding the most probable explanation of the nature of suffering and sentience in general?

Robert Daoust: For what it may be worth, I think I have a unique perspective in the field of psychoneural research because I’m a self-taught independent scholar, specialized in a topic, suffering, that has not been systematically approached until now within the framework of a modern scientific discipline. The closest relevant knowledge I could find in the academic world was pain science. By chance, McGill University in my hometown had perhaps the best pain research community, around which I hung out for several years and learned a lot.

I hold a few things as pretty certain: 1) the brain stem is more essential to sentience than the cortex; 2) the emergence of sentience depends on electromagnetic wave-fields generated in the brain, more than on computations made by neurons; 3) the solution to the hard problem of consciousness requires an explanation at the right level of emergence, the psychological level, but based on previous levels described by biology, chemistry, physics.

Sentient experience is made possible by evolution through the advent of complex systems of cells specialized in electrical activities. Those activities represent insentient sensory, motor, or associative activities. In spite of their sophistication, insects “probably” behave without sentience, thanks only to their deep learning neural networks. But within vertebrates and some invertebrates the electromagnetic representations become so numerous and well interrelated that they form a complex blob or wave-field where a theater of meaning-values can take place: qualia constitute streams of interrelationships where they mean-and-are-worth something to each other, within a “narrative”.

I hypothesize that the value part has its physical substratum in forces of attraction and repulsion taking various symmetric and dissymmetric configurations. The meaning part depends on neural computations and it cannot be conscious without value. We suffer because it contributes to survival. The most basic evolutive tendencies are entropy and negentropy, i.e. de-struction and con-struction. A single bacteria cell, for instance, undergoes a tension that brings it toward a nutrient or away of a threat. In a billion cell organism like ours, a specialized system is at work and contributes to -struction.

Sentience Research: So, in your view, how broad is “we”, when we speak of us all, the sentient beings who suffer?

Robert Daoust: My feeling is that as a matter of fact there is no ‘’I’’ that feels. Each suffering is an independent instance of sentience. The “I” as the owner of consciousness is an illusion, but socially it represents a convenient fictional agent, often self-aggrandized by identification to various “we”. Technically, the experience, the content of experience, and the subject of experience are just and simply one and the same thing (see Strawson). Sentience, I like to say, is what it feels like to be an electromagnetic wavefield under certain circumstances. So… the extent of sentience, as far as we can tell, would be that it emerged on earth millions of years ago, it probably emerged also in countless places elsewhere in the universe, and in the far future it will probably emerge in all matter-energy that can be used for that purpose.

That’s why antinatalism, nihilism, despair are useless as a solution. Rather than count on the end of wicked species like ours, we’d do better to count on the better angels of our nature and try to sustainably organize the alleviation of suffering.

Sentience Research: Do you think suffering can be quantified? How to relate the intensity of suffering with the number of individuals affected? How do we decide to take action over one case of suffering instead of over another when the number of individuals affected and the intensity of their sufferings are different in both cases?

Robert Daoust: Yes, quantifying suffering is not impossible, like many say, but it is not as easy as others seem to think. Algometry is a whole discipline by itself, for which I made those Preparatory Notes for the Measurement of Suffering. I invite interested readers to look at that document. It will take several million dollars to seriously start algometry as a subdiscipline of algonomy.

Sentience Research: Tell us something more about the current situation of the Algosphere. How does it work and what do you expect from it? What are the bottlenecks for achieving its goals?

Robert Daoust: The Algosphere Alliance has been in operation for seven years now. It invites everybody to gather and make sure that suffering is now under siege, encircled, approached from all sides… Some fifty persons have become allies, and a hundred others have registered on the website. Six organizations are also allies. It’s a slow but solid start. A main component of the Alliance is its Collaborative Platform, where everyone does what they find interesting. Various things have been growing there, mostly underground. Since last April, a major revamping of the Algosphere is underway, with a committee of five people working hard. The goal is to rethink the whole substance and form in order to make the general public understand what is going on in the Algosphere. More news on this coming soon… We expect that during this century, thanks to our allies, suffering will become a priority for most people on this planet, when it is a question of making important collective or individual decisions. If there is one bottleneck for achieving this goal, it is the challenge of cultural change: how can the hearts and minds become involved in a global collective operation to restrain the phenomenon of suffering? Plans are set up, let’s hope they work.

Sentience Research: What are the strategies for abolishing suffering, and what can we do today as a movement?

Robert Daoust: The strategies have been spelled out by David Pearce in his masterpiece The Hedonistic Imperative. Essentially, we should investigate the biological or genetic factors that are to blame for the apparition of suffering and from there we should build a better arrangement of the cellular or sub-cellular components of our psyche. Meanwhile, social and political action may also be necessary, although insufficient, for reaching the goal. The road ahead is relatively clear and simple, although fraught with obstacles. The main obstacle might be a collapse of civilization through one of the existential risks. Another obstacle might be that suffering represents an essential part of the normal and free functioning of sentience: we might build organisms that feel no suffering at all, but in my opinion they would self-destruct, if their behaviour is not technically constrained, because of the inherent negentropic will to power that makes every entity do everything it can to con-struct itself. In a sentient organism, the ultimate regulator is unbearable suffering. To overcome that obstacle we would have to ensure that resurrection is available, that pain-free-and-free-choosing sentient beings are immortal.

In any case, each of us who realizes the importance of controlling the phenomenon of suffering can act through the various suffering-focused organizations that appeared recently:

And all of us who understand the value of synergy can join together in the Algosphere Alliance. Many other projects remain to be set up, for instance:

- Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential: we have to harness this crucial resource for improving our world on a global level.

- Toward an Institute of Algonomy: we cannot go far without such an institutional basis for systematic knowledge, bibliography, taxology, algometry, strategic analysis, etc.

- “Alleviating my suffering”: this is a project, at Algosphere, of an Information and Resources Center for responding to individuals’ requests.

- Algomedia: this is another project at Algosphere, concerning the use of all kinds of media for popularizing suffering-focused news and activities.

- Global strategy project: this is still to be developed, it has to do with the junction of various groups, like effective altruism, Buddhism, compassion research, etc. around some kind of political program.

- Action-Teams for an organized minimization of inacceptable sufferings: this is a recent version of a project that I have been trying to set up for decades in order to link direct practical action and the systematic control of suffering.

Sentience Research: Is there anything left to say? What else should we talk about in this interview for it to be a complete review of your more important thoughts and actions?

Robert Daoust: Faith in God was important for me until I was seventeen. I wanted to become a saint, and a priest. I lost faith, mainly because of the absurd idea of an eternal hell created by an infinitely loving father. Also because modern science made more sense for explaining the world. I was especially impressed by a book in 1966 Les prodigieuses victoires de la psychologie moderne. I tried to recover a kind of faith until my mid-thirties, studying oriental religions and parapsychology, before concluding that nothing, in those spiritual realms, stands up against scrutiny. Now I believe there are more things in material matter than are dreamt of by philosophers and mystics.

Soon, I will meet with colleagues I knew at school some 55 years ago. I realize that I was a poor kid as a student, and I remained poor all my life, inadvertently following the vow of poverty. I did not have children. It was long before I met girls, in my twenties. I was for good in a couple between the ages of 44 and 69. Fortunately, my brothers and sisters have all been a blessing for me, and most of my dearest friends too, intellectually, financially, socially, emotionally. My main problem in my twenties, besides finding a girl and a god, was to find a career. I settled for being a ‘thinker’, because being a philosopher or a writer was too demanding for me. And I settled for discovering something, because this is the most efficient work one can do: for instance as a pot maker you can make a number of pots in your life, but as the inventor of the pot making machine you produce an incomparably greater number of pots.

I really fear only one thing: that there be an eternal hell for any sentient being. I cannot stand that thought for more than a few seconds. I think that this is a fundamental fact of human life: everyone meets unbearable suffering, for instance as a child who puts a hand on the stove burner, but also sooner, probably as a newborn or even as a foetus. Discovering unbearable suffering is incredibly and very fundamentally traumatic. Not only we cannot do or have all what we want, but also we may be overpowered by something that is terribly awful, that will make us suffer endlessly. We all are affected by post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s so terrible, we should forget about it, shouldn’t we? What’s on TV tonight?

Nevertheless, there are other important things in life besides the question of suffering: everything we love. I retained from my religious education that the object of true love takes the status of the sacred, of what we want to be holy, whole, well con-structed rather than awfully de-structed. I love those who are close and dear to me, I love science and knowledge, I love beauty and pleasure and the glorious power that I find beneficial, and I love forests, mountains, lakes, rivers, and seas and skies…

Sentience Research: Thank you very Much Robert, it has been a pleasure.

Robert Daoust: Thank you for giving me the opportunity to express my thoughts, the pleasure was mine too.

Recent Comments