Measuring Sentience

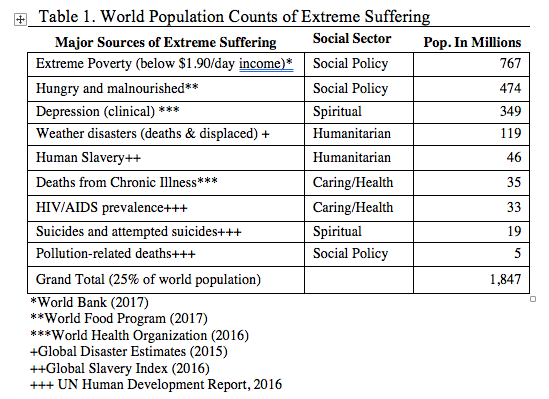

Measurement and estimation are of prime importance for most rational activities dealing with suffering, and quantitative studies concerning suffering should be developed as an independent subdiscipline, which could be called algometry.

Empathetic verbal feedback from others has been shown to alleviate the intensity of experimental pain on an experiment on pain perception and empathy in humans.

In the experiment they created a dedicated setup mimicking a medical environment where people enduring painful stimuli received empathetic or unempathetic comments from others. Positive (empathetic) feedback was able to reduce pain intensity perception, in agreement with previous theoretical models and experimental studies, while negative (unempathetic) feedback did not induce consistent changes in pain intensity reports.

Placebos are so effective that placebo placebos work: A pain cream with no active ingredients worked even when not used by the patient. Just owning the cream was enough to reduce pain.

There are two very related questions: “Is there a symmetry between suffering and enjoyment?” and “Can suffering be compensated with enjoyment?”

Investigating the way in which we respond to these questions is very relevant, since we may have biases or blindness that are encouraging to make bad decisions, such as the survivorship bias. By better understanding and evaluating suffering and enjoyment we can more easily minimize suffering and maximize enjoyment, as well as compensate for bad experiences, if such a thing were possible.

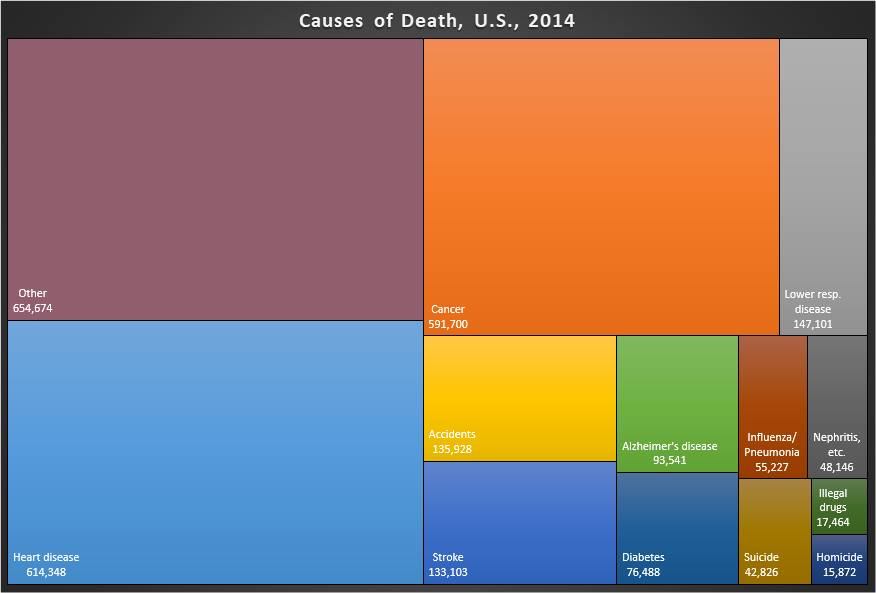

What’s killing us? I made the following graph. I include the top ten causes of death in the U.S., plus homicide and illegal drug overdoses, because the latter two are actually discussed in political discourse.

Observations:

1. The top causes of death almost never appear in political discourse or discussions of social problems. They’re almost all diseases, and there is almost no debate about what should be done about them. This is despite that they are killing vastly more people than even the most destructive of the social problems that we do talk about. (Illegal drugs account for 0.7% of the death rate; murder, about 0.6%.)

2. This is not because there is nothing to be done about the leading causes of death. Changes in diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes can make very large differences to your risk of heart disease, cancer, and other major diseases, and this is well-known.

3. It’s also not because it’s uncontroversial what we should do about them, or because everybody already knows. The government could, for example, try to discourage tobacco smoking, alcohol use, and overeating, and encourage exercise. There are many ways this could be attempted. Perhaps the government could spend more money on trying to cure the leading diseases. There obviously are policies that could attempt to address these problems, and it would certainly not be uncontroversial which ones, if any, should be adopted. Those who support social engineering by the government might be expected to be campaigning for the government to address the things that are killing most of us.

4. Most of these leading killers are themselves mainly caused by old age. If “Old Age” were a category, it would be causing by far the majority of deaths. Again, it’s not the case that nothing could be done about this. We could be doing much more medical research on aging.

5. It’s also not that we just don’t care about diseases. *Some* diseases are treated as political issues, such that there are activists campaigning for more attention and more money to cure them. There are AIDS activists, but there aren’t any nephritis activists. There are breast cancer walks, but there aren’t any colon cancer walks.

6. Hypothesis: We don’t much care about the good of society. Refinement: Love of the social good is not the main motivation for (i) political action, and (ii) political discourse. We don’t talk about what’s good for society because we want to help our fellow humans. We talk about society because we want to align ourselves with a chosen group, to signal that alignment to others, and to tell a story about who we are. There are AIDS activists because there are people who want to express sympathy for gays, to align themselves against conservatives, and thereby to express “who they are”. There are no nephritis activists, because there’s no salient group you align yourself with (kidney disease sufferers?) by advocating for nephritis research, there’s no group you thereby align yourself *against*, and you don’t tell any story about what kind of person you are.

In conclusion, this sucks. Because we actually have real problems that require attention. If we won’t pay attention to a problem just because it kills a million people, but we need it also to invoke some ideological feeling of righteousness, then the biggest problems will continue to kill us. And by the way, the smaller problems that we actually pay attention to probably won’t be solved either, because all our ‘solutions’ will be designed to flatter us and express our ideologies, rather than to actually solve the problems.

Cold receptors primarily react to temperatures ranging from 68 to 86˚F, while warm receptors are activated between 86˚F and 104˚F. At extreme temperatures—below 60˚F and beyond 113˚F—the temperature signal is accompanied by a sensation of pain. Weirdly, researchers have discovered that at temperatures greater than 113˚F, some cold receptors can also fire.

The majority of scientists support the theory that paradoxical cold is a malfunction of the thermoreceptor system. Evidence suggests that pain receptors that respond to potentially harmful heat levels coexist on the same sensory fibers as cold thermoreceptors, says Lynette Jones, a senior research scientist at MIT. So when the nerve fiber sends a signal to the brain, it can sometimes be misinterpreted as a sensation of extreme cold. Paradoxical cold is the “strange operation of a system under unusual stimulation conditions,” she says… Read more

We usually start measuring what we can measure well, and we lack motivation to try to measure what we cannot measure well. In this way, the measurement makes invisible the elements that are more difficult to measure although they could be much more relevant. This increases the risk of ignoring those other elements and even in some cases, promoting the idea that they do not exist. The death toll (number of deaths) in an accident or in a conflict can make suffering -much more difficult to measure- invisible. For example, surely 10 individuals who die burned alive in an aviation accident, as a whole, suffer much more than 100 individuals who die from concussion. But suffering is difficult to measure and attention goes to the number we can easily get. This could cause the establishment of wrong priorities… Read more