“We replicate nine key results from the happiness literature: the Easterlin Paradox, the ‘U-shaped’ relation between happiness and age, the happiness trade-off between inflation and unemployment, cross-country comparisons of happiness, the impact of the Moving to Opportunity program on happiness, the impact of marriage and children on happiness, the ‘paradox’ of declining female happiness, and the effect of disability on happiness. We show that none of the findings can be obtained relying only on nonparametric identification. The findings in the literature are highly dependent on one’s beliefs about the underlying distribution of happiness in society, or the social welfare function one chooses to adopt. Furthermore, any conclusions reached from these parametric approaches rely on the assumption that all individuals report their happiness in the same way. When the data permit, we test for equal reporting functions, conditional on the existence of a common cardinalization from the normal family. We reject this assumption in all cases in which we test it.”

Measuring Sentience

In Simon Knutsson‘s words:

That happiness and suffering are measurable, in principle, to the extent that is required to talk about the net balance among several individuals is highly controversial and widely rejected. That is, it is controversial that they are (in principle) measurable to the required degree in an objective, non-arbitrary, scientific way that does not involve value judgements on the part of the person doing the measurement. One could say “I assign number –10 to Ann’s suffering and +5 to Ben’s happiness, and then I add them together. These numbers are intertwined with my values, and others might assign different numbers depending on their values.” Although that might be the best we can do, it does not count as measurement in the objective sense that we are concerned with […].

Economist Yew-Kwang Ng says that the following statement is representative of the typical economics textbook view: “Today, no one really believes that we can actually measure utils.” He continues that the probably most widely used textbook says that “economists today generally reject the notion of a cardinal, measurable, utility.” For the kinds of claims discussed above, we would need utilities to be measurable on a strong kind of interpersonal cardinal scale (an interpersonally additive ratio scale), which is widely rejected by economists.

Ng adds that this skepticism about measurability is also “very common” among “sociologists and psychologists who study happiness.”

Some history is interesting here. The early utilitarians of the 19th century, such as John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick, did not seem worried by interpersonal comparisons of utility. But as Bergström points out, “in the 20th century, things have changed a great deal. Now the dominant view — at least among economists — seems to be that interpersonal comparisons of utility are impossible or necessarily subjective and unscientific.”

Of course, there is not complete consensus on the matter; some believe that happiness and suffering (or utility) can be measured to the extent required to talk about the net balance or amounts among several individuals. Philosophers generally seem to be somewhat more optimistic than economists.

Source: https://foundational-research.org/measuring-happiness-and-suffering/

In Magnus Vinding‘s [1] words [2]:

I think there is a problem with underspecified [in expressions] like “more suffering than happiness” […] For example, talking about “whether suffering or enjoyment is more common” (in this piece [3]) sounds rather descriptive, whereas saying that, or whether, “suffering predominates” (ibid.) will often have evaluative and/or moral connotations. The same is true of a term like welfare: it often has an evaluative/axiological meaning as opposed to a purely descriptive one (see e.g. sec. 1.1.1 here: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/92027/3/Mathison_Eric_201811_PhD_thesis.pdf [4]).

Indeed, the question as to “whether suffering predominates” can mean at least three very different things […]

For one, it may refer to a purely descriptive statement: there is a greater quantity of happiness than suffering, by some given measure. (And this, in turn, implies further questions concerning how one indeed measures happiness and suffering, in particular how one measures them against each other, and whether they are even commensurable, not just evaluatively but also in purely descriptive terms, cf. https://foundational-research.org/measuring-happiness-and-suffering/ [5] and https://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol1/iss7/18/ [6])

Second, it may mean something along evaluative lines such as “there is more positive value than negative value” in the existing happiness and suffering respectively. And this is a very different claim in that one can claim there is far more happiness than suffering in the world, by some given measure, yet still maintain that the disvalue of the suffering is far greater than the value of the happiness. Indeed, quite a number of philosophers and traditions in the East (cf. http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2015/12/Breyer-Axiology-final.pdf [7]) and the West (including Epicurus and Schopenhauer) have defended views according to which the disvalue of suffering dominates that of happiness entirely; for recent defenses of such views, see Gloor: https://foundational-research.org/tranquilism/ [8] and Wolf: https://jwcwolf.public.iastate.edu/Papers/JUPE.HTM [9].

Third, one can think there is far more happiness than suffering in the world, even in evaluative terms, yet still think the suffering carries much greater moral/deontic significance; asymmetries of this kind have in fact been defended by quite a few prominent philosophers, including W. D Ross, cf. sec. 2.5 here: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/92027/3/Mathison_Eric_201811_PhD_thesis.pdf [10]

Beyond that, there are also issues concerning intra and inter-personal trade-offs: even if most lives in nature contain far more happiness than suffering (by some assumed measure), this would not mean that the happiness of some beings can ever outweigh the suffering of others, either in evaluative terms or deontic terms. Many ethicists accept intra-personal trade-offs while rejecting inter-personal ones (for instance Richard Ryder and Stevan Harnad, and to some extent Jamie Mayerfeld).

The perhaps most important question to ponder deeply, in my view, is whether we think any amount of happiness can morally outweigh the very worst of suffering. I have argued in the negative: https://magnusvinding.com/2018/09/03/the-principle-of-sympathy-for-intense-suffering/ [11] and so have philosophers Jamie Mayerfeld, Joseph Mendola, Ingemar Hedenius, and Ragnar Ohlsson, among others.

Just thought this was worth pointing out. Notions of “net negative” and “net positive” lives — as pertaining both to single individuals and (especially) to groups — require serious unpacking in terms of their meaning and assumed evaluative and moral implications.

Links and references

[1] https://magnusvinding.com/

[2] https://www.facebook.com/groups/suffering.in.nature/permalink/2727855270577587/

[3] http://www.zachgroff.com/2019/06/how-much-do-wild-animals-suffer.html

[4] https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/92027/3/Mathison_Eric_201811_PhD_thesis.pdf

[5] https://foundational-research.org/measuring-happiness-and-suffering/

[6] https://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol1/iss7/18/

[7] http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2015/12/Breyer-Axiology-final.pdf

[8] https://foundational-research.org/tranquilism/

[9] https://jwcwolf.public.iastate.edu/Papers/JUPE.HTM

[10] https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/92027/3/Mathison_Eric_201811_PhD_thesis.pdf

[11] https://magnusvinding.com/2018/09/03/the-principle-of-sympathy-for-intense-suffering/

“I was burned so severely and in so much pain that I did not want to live even in the early moments following the explosion. A man who heard my shouts for help came running down the road, I asked him for a gun. He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Can’t you see I am a dead man? I am going to die anyway. I need to put myself out of this misery.’ In a very kind and compassionate caring way, he said, ‘I can’t do that.'”

“We might give more weight to the judgments of those who have already been tortured, since their evaluations of the experiences are presumably more accurate. Unfortunately, here too people may forget the severity of their past suffering. This empathy gap often happens to me when I think back on my own past experiences of intense suffering, unable to conjure up feelings of how awful I felt at the time.” (Brian Tomasik)

“Sometimes people who suffer enormously do look back and judge that their suffering wasn’t worth it. Consider the case of Dax Cowart, who suffered so badly that he wished he had been killed, even in retrospect.”

I’ve never had a kidney stone. Thank God. According to Quora responses to the question “How painful are kidney stones?” they are about as painful as it gets. They’re the most painful thing a person can experience naturally, leaving aside torture and violent body-dismembering events. Many say they often get to be “10/10 pain”. That’s clearly an ethical catastrophe given that 10% of people experience them at least once during their lifetime.

Someone described the experience of having a kidney stone as “indistinguishable from being stabbed with a white-hot-glowing knife that’s twisted into your insides non-stop for hours”.

I wonder whether from a compassionate (utilitarian/consequentialist) point of view, it would *really* pay off to have as a priority “adopt a life-style that minimizes the chances of kidney stones”.

It’s likely that the reason why we do not hear about this is because (1) trauma often leads to suppressed memories, (2) people don’t like sharing their most vulnerable moments, and (3) memory is state-dependent (you cannot easily recall the pain of kidney stones for the same reason you can’t recall the qualia of your LSD trip: you’ve lost a tether/handle/trigger for it, as it is an alien state-space on a wholly different scale of intensity than everyday life). If so, maybe that’s to our detriment. Perhaps it’s worth taking these reports *very* seriously, lest we become victims ourselves.

A typical used mattress may have anywhere from 100,000 to 10 million mites inside.

In 2013, Tor Wager, a neuroscientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, took the logical next step by creating an algorithm that could recognize pain’s distinctive patterns; today, it can pick out brains in pain with more than ninety-five-per-cent accuracy. When the algorithm is asked to sort activation maps by apparent intensity, its ranking matches participants’ subjective pain ratings. By analyzing neural activity, it can tell not just whether someone is in pain but also how intense the experience is. “What’s remarkable is that basic pain signals seem to look pretty much the same across a wide variety of people,” Wager said. “But, within that, different brain systems are more, or less, significant, depending on the individual.”

Among the brain’s many pain-producing patterns, however, there is only one region that is consistently active at a high level: the dorsal posterior region of the insula. Using a new imaging technique, Tracey and one of her postdoctoral fellows, Andrew Segerdahl, recently discovered that the intensity of a prolonged painful experience corresponds precisely with variations in the blood flow to this particular area of the brain. In other words, activity in this area provides, at last, a biological benchmark for agony. Tracey described the insula, an elongated ridge nestled deep within the Sylvian fissure, with affection. “It’s just this lovely island of cortex hidden in the middle, deep in your brain,” she said. “And it’s got all these amazing different functions. When you say, ‘Actually, I feel a bit cold, I need to put a sweater on,’ what’s driving you to do that? Probably this bit.”

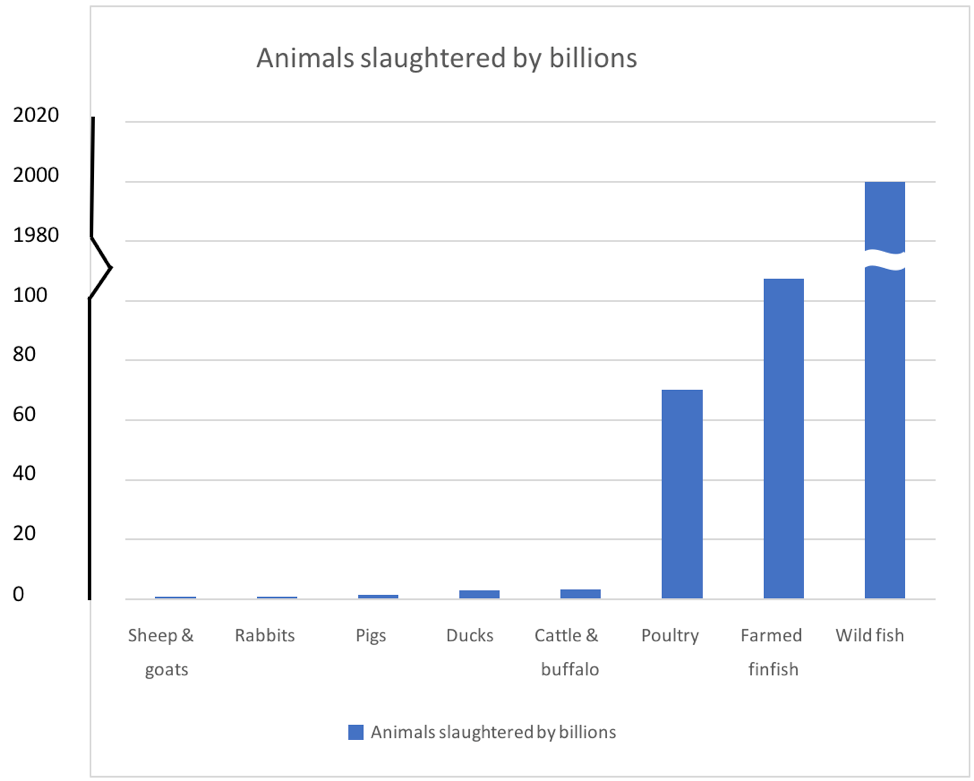

There has historically been almost no effort made to reduce the inhumaneness of fish slaughter. The majority of fish are killed without stunning, by asphyxiation either in the air or on the ice. One study found that it takes common species of fish 55-250 minutes to die via asphyxiation. Fish that aren’t asphyxiated often die by being live gutted; the same study found that live gutting can take up to 25-65 minutes to kill the fish. Fish who are stunned are typically struck on the head (percussive stunning), stunned electrically, or stunned using gas. Pre-slaughter stunning is more common in wealthier nations (like the UK, Northern Europe, Chile, Canada, and Australia) and for high-value species (like salmon and trout).

Two hundred ninety-one lay persons and 10 forensic pathologists rated the lethality, time, and agony for 28 methods of suicide for 4117 cases of completed suicide in Los Angeles County in the period 1988-1991. Whereas pathologists provided consistent ratings, lay persons demonstrated extreme variability and a tendency to inflate ratings of all three dimensions. Significant gender differences emerged, with females rating frequently used suicide methods more similarly to pathologists than the males did. Males who suicided used the most lethal and quickest methods whereas females selected methods varying in lethality, duration, and agony. African Americans were overrepresented in the use of the most lethal and quickest methods.