…it is common to access some memory of adolescence and to be ashamed of oneself, of what we did or even of what we thought at that moment. It seems as if someone else has done it. It can become humiliating or almost inconceivable that we would have been able to think or do such a thing. But this is explained simply if we accept that we are precisely talking about another person: my “I of the past”. Every millisecond (or minimum unit of time) we are a different person. This is called Empty Individualism.

The Simurgh features strongly in Persian mythology and a number of the great epic poems of Persian literature. It is said to be a mixture of peacock, griffon and lion symbolises the union of heaven and earth.

In his epic poem The Conference of the Birds, Fariduddin Attar describes how millions of birds went in search for their perfect king, the great bird Simurgh. Many of the birds were killed during their ordeals in search of the Simurgh – climbing high peaks and plunging into dark valleys as well as fighting their own doubts and fears.

At the end of their search only thirty birds remain to reach the gates of Simurgh’s palace. They all alight onto the throne or masnad which is described as being the seat of the Majesty and the Glory. The throne, however, remains empty and there is no sign of the Simurgh. It then becomes clear to the birds, through an inner glow which spreads through them all, that they, together, make up the Presence of the Simurgh and that the Simurgh is really just their joint presence. A literal translation of Simurgh is “Thirty Birds”.

They embark upon the nearly infinite adventure. They pass through seven valleys or seas; the name of the penultimate is Vertigo; the last, Annihilation. Many pilgrims give up; others perish. Thirty, purified by their efforts, set foot on the mountain of the Simurgh. At last they gaze upon it: they perceive that they are the Simurgh and that the Simurgh is each one of them and all of them. In the Simurgh are the thirty birds and in each bird is the Simurgh.

Trialism in philosophy was introduced by John Cottingham as an alternative interpretation of the mind–body dualism of Rene Descartes. Trialism keeps the two substances of mind and body, but introduces a third substance, sensation, belonging to the union of mind and body. This allows animals, which do not think like humans, to be regarded as having sensations and not as being mere automata.

Although composed of two substances, mind and body, the human being possesses distinctive attributes in its own right (including sensations, passions, emotions), and these form a third category, that cannot be reduced to thought or extension.[3] Cottingham has also argued that Descartes’s view of animals as ‘machines’ does not have the reductionistic implications commonly supposed.[4] Finally, Cottingham has explored the importance of Descartes as a moral philosopher, with a comprehensive picture of the good life that draws both on his scientific work (in physiology and psychology) and also on the theistic outlook that informs all his philosophy.[5] Cottingham is co-editor and translator of the three-volume Cambridge edition of The Philosophical Writings of Descartes.[6]

Kong Derick has also introduce the term Derician Trialism, in which he maintains the two substances of mind and body of Descartes and substituted the sensation substance of Cottingham due to it limitations, with the substance he calls Submind, which involves the processes of memories, sensations, emotions and reflexes. He also says that animals do have a submind which makes them to be subconscious.

“Alex had a vocabulary of over 100 words, but was exceptional in that he appeared to have understanding of what he said. For example, when Alex was shown an object and was asked about its shape, color, or material, he could label it correctly. He could describe a key as a key no matter what its size or color, and could determine how the key was different from others. Looking at a mirror, he said “what color”, and learned “grey” after being told “grey” six times. This made him the first and only non-human animal to have ever asked a question—and an existential question at that. (Apes who have been trained to use sign-language have so far failed to ever ask a single question.) Alex’s ability to ask questions (and to answer to Pepperberg’s questions with his own questions) is documented in numerous articles and interviews.

Alex was said to have understood the turn-taking of communication and sometimes the syntax used in language. He called an apple a “banerry” (pronounced as rhyming with some pronunciations of “canary”), which a linguist friend of Pepperberg’s thought to be a combination of “banana” and “cherry”, two fruits he was more familiar with.

Alex could add, to a limited extent, correctly giving the number of similar objects on a tray. Pepperberg said that if he could not count, the data could be interpreted as his being able to estimate quickly and accurately the number of something, better than humans can. When he was tired of being tested, he would say “Wanna go back”, meaning he wanted to go back to his cage, and in general, he would request where he wanted to be taken by saying “Wanna go…”, protest if he was taken to a different place, and sit quietly when taken to his preferred spot. He was not trained to say where he wanted to go, but picked it up from being asked where he would like to be taken.

If the researcher displayed irritation, Alex tried to defuse it with the phrase, “I’m sorry.” If he said “Wanna banana”, but was offered a nut instead, he stared in silence, asked for the banana again, or took the nut and threw it at the researcher or otherwise displayed annoyance, before requesting the item again. When asked questions in the context of research testing, he gave the correct answer approximately 80 percent of the time.”

Sponge (source)

Trichoplax adhaerens / Placozoa (source)

“I was burned so severely and in so much pain that I did not want to live even in the early moments following the explosion. A man who heard my shouts for help came running down the road, I asked him for a gun. He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Can’t you see I am a dead man? I am going to die anyway. I need to put myself out of this misery.’ In a very kind and compassionate caring way, he said, ‘I can’t do that.'”

“We might give more weight to the judgments of those who have already been tortured, since their evaluations of the experiences are presumably more accurate. Unfortunately, here too people may forget the severity of their past suffering. This empathy gap often happens to me when I think back on my own past experiences of intense suffering, unable to conjure up feelings of how awful I felt at the time.” (Brian Tomasik)

“Sometimes people who suffer enormously do look back and judge that their suffering wasn’t worth it. Consider the case of Dax Cowart, who suffered so badly that he wished he had been killed, even in retrospect.”

I’ve never had a kidney stone. Thank God. According to Quora responses to the question “How painful are kidney stones?” they are about as painful as it gets. They’re the most painful thing a person can experience naturally, leaving aside torture and violent body-dismembering events. Many say they often get to be “10/10 pain”. That’s clearly an ethical catastrophe given that 10% of people experience them at least once during their lifetime.

Someone described the experience of having a kidney stone as “indistinguishable from being stabbed with a white-hot-glowing knife that’s twisted into your insides non-stop for hours”.

I wonder whether from a compassionate (utilitarian/consequentialist) point of view, it would *really* pay off to have as a priority “adopt a life-style that minimizes the chances of kidney stones”.

It’s likely that the reason why we do not hear about this is because (1) trauma often leads to suppressed memories, (2) people don’t like sharing their most vulnerable moments, and (3) memory is state-dependent (you cannot easily recall the pain of kidney stones for the same reason you can’t recall the qualia of your LSD trip: you’ve lost a tether/handle/trigger for it, as it is an alien state-space on a wholly different scale of intensity than everyday life). If so, maybe that’s to our detriment. Perhaps it’s worth taking these reports *very* seriously, lest we become victims ourselves.

A typical used mattress may have anywhere from 100,000 to 10 million mites inside.

In 2013, Tor Wager, a neuroscientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, took the logical next step by creating an algorithm that could recognize pain’s distinctive patterns; today, it can pick out brains in pain with more than ninety-five-per-cent accuracy. When the algorithm is asked to sort activation maps by apparent intensity, its ranking matches participants’ subjective pain ratings. By analyzing neural activity, it can tell not just whether someone is in pain but also how intense the experience is. “What’s remarkable is that basic pain signals seem to look pretty much the same across a wide variety of people,” Wager said. “But, within that, different brain systems are more, or less, significant, depending on the individual.”

Among the brain’s many pain-producing patterns, however, there is only one region that is consistently active at a high level: the dorsal posterior region of the insula. Using a new imaging technique, Tracey and one of her postdoctoral fellows, Andrew Segerdahl, recently discovered that the intensity of a prolonged painful experience corresponds precisely with variations in the blood flow to this particular area of the brain. In other words, activity in this area provides, at last, a biological benchmark for agony. Tracey described the insula, an elongated ridge nestled deep within the Sylvian fissure, with affection. “It’s just this lovely island of cortex hidden in the middle, deep in your brain,” she said. “And it’s got all these amazing different functions. When you say, ‘Actually, I feel a bit cold, I need to put a sweater on,’ what’s driving you to do that? Probably this bit.”

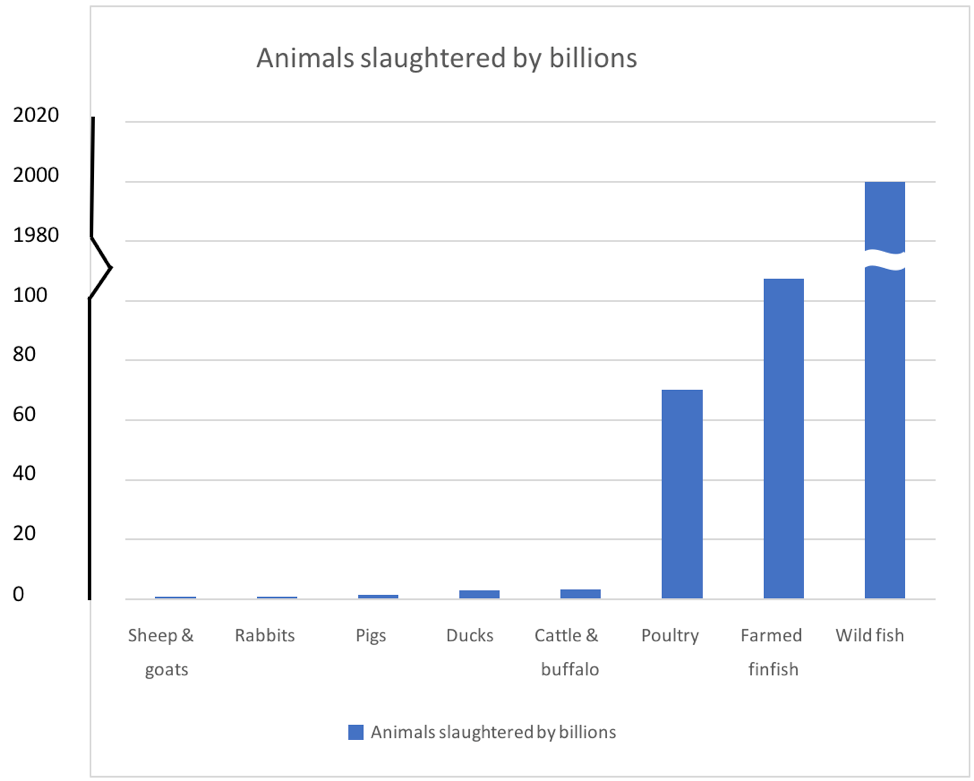

There has historically been almost no effort made to reduce the inhumaneness of fish slaughter. The majority of fish are killed without stunning, by asphyxiation either in the air or on the ice. One study found that it takes common species of fish 55-250 minutes to die via asphyxiation. Fish that aren’t asphyxiated often die by being live gutted; the same study found that live gutting can take up to 25-65 minutes to kill the fish. Fish who are stunned are typically struck on the head (percussive stunning), stunned electrically, or stunned using gas. Pre-slaughter stunning is more common in wealthier nations (like the UK, Northern Europe, Chile, Canada, and Australia) and for high-value species (like salmon and trout).